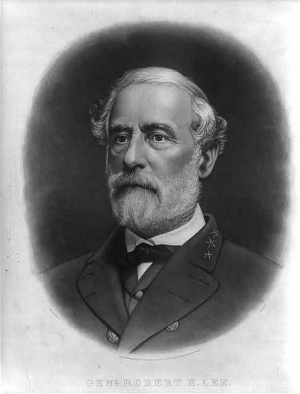

Robert E. Lee

|

Robert Edward Lee (1807-1870) - Born 19 Jan 1807, died 12 Oct 1870. He was a career army officer and the most successful general of the Confederate forces during the U.S. Civil War. He eventually commanded all Confederate armies as general-in-chief. After the war, he urged reconciliation and spent his final years as a progressive college president.  Early YearsLee was born at Stratford Hall Plantation, in Westmoreland County, Virginia, the fourth child of Revolutionary War hero Henry Lee ("Lighthorse Harry") and Anne Hill (Carter) Lee. He entered the United States Military Academy in 1825. When he graduated (second in his class of 46) in 1829 he had not only attained the top academic record but was the first cadet (and so far the only) to graduate the Academy without a single demerit. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Army Corps of Engineers. While he was stationed at Fort Monroe, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis (1808-1873), the great-granddaughter of Martha Washington, at Shirley Plantation in Charles City County, Virginia, where she had been born. They lived in the Custis-Lee Mansion, which today is Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial on the banks of the Potomac River in Arlington County, Virginia, just across from Washington, D.C. They eventually had three sons and four daughters: George Washington Custis Lee, William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, Robert Edward, Mary, Agnes, Annie, and Mildred.

Mexican WarLee's service during the Mexican War (1846-1848) was so outstanding that he was promoted twice and served as one of Gen. Winfield Scott's chief aides. He was instrumental in several American victories through his personal reconnaissance as a staff officer. He was promoted to major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo in April 1847. He also fought at Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec, and was wounded at the latter. By the end of the war, he had been promoted to lieutenant colonel. Superintendent of the United States Military AcademyDuring his three years at West Point (1852-1855), he improved the buildings and the courses. Lee's oldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, attended West Point during his tenure. Custis Lee graduated in 1854, first in his class. Harper's FerryLee happened to be in Washington in 1859 at the time of John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia and was sent there to arrest Brown and to restore order. He did this very quickly and then returned to his regiment in Texas. When Texas seceded from the Union in 1861, Lee was called to Washington, DC to wait for further orders. U.S. Civil WarThe beginning (1861-1862) On April 18, 1861, on the eve of the American Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln, through Secretary of War Simon Cameron, offered Lee command of the United States Army (Union Army) through an intermediary. Lee's sentiments were against secession but his loyalty to his native Virginia led him to join the Confederacy. At the outbreak of war, he was appointed to command all of Virginia's forces, and then as one of the first five full generals of Confederate forces. After commanding Confederate forces in western Virginia, and then in charge of coastal defenses along the Carolina seaboards, he became military adviser to Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy, who he knew at West Point. Commander, Army of Northern Virginia (1862-1865) Following the wounding of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston at the Battle of Seven Pines, on June 1, 1862, Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia, his first opportunity to lead an army in the field. He soon launched a series of attacks, the Seven Days Battles, against General George B. McClellan's Union forces threatening the Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia. Lee's attacks resulted in heavy Confederate casualties and they were marred by clumsy tactical performances by his subordinates, but his aggressive actions unnerved McClellan. After McClellan's retreat, Lee defeated another Union army at the Second Battle of Bull Run. He then invaded Maryland, hoping to replenish his supplies and possibly influence the Northern elections that fall in favor of ending the war. McClellan obtained a lost order that revealed Lee's plans and brought superior forces to bear at Antietam before Lee's army could be assembled. In the bloodiest day of the war, Lee withstood the Union assaults but withdrew his battered army back to Virginia. Disappointed by McClellan's failure to destroy Lee's army, Lincoln named Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside ordered an attack across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg. Delays in getting bridges built across the river allowed Lee's army ample time to organize strong defenses, and the attack on December 12, 1862, was a disaster for the Union. Lincoln then named Joseph Hooker commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker's advance to attack Lee in May 1863, near Chancellorsville, Virginia, was defeated by Lee and Stonewall Jackson's daring plan to divide the army and attack Hooker's flank. It was an enormous victory over a larger force but came at a great cost as Jackson, Lee's best subordinate, was mortally wounded. In the summer of 1863, Lee proceeded to invade the North again, hoping for a Southern victory that would compel the North to grant Confederate independence. But his attempts to defeat the Union forces under George G. Meade at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, failed. His subordinates did not attack with the aggressive drive Lee expected, J.E.B. Stuart's cavalry was out of the area, and Lee's decision to launch a massive frontal assault on the center of the Union line—the disastrous Pickett's Charge—resulted in heavy losses. Lee was compelled to retreat again but, as after Antietam, was not vigorously pursued. Following his defeat at Gettysburg, Lee sent a letter of resignation to Confederate President Jefferson Davis on August 8, 1863, but Davis refused Lee's request. In 1864, the new Union general-in-chief Ulysses S. Grant sought to destroy Lee's army and capture Richmond. Lee and his men stopped each advance, but Grant had superior reinforcements and kept pushing each time a bit further to the southeast. These battles in the Overland Campaign included the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House, and Cold Harbor. Grant eventually fooled Lee by stealthily moving his army across the James River. After stopping a Union attempt to capture Petersburg, Virginia, a vital railroad link supplying Richmond, Lee's men built elaborate trenches and were besieged in Petersburg. He attempted to break the stalemate by sending Jubal Anderson Early on a raid through the Shenandoah Valley to Washington, D.C., but Early was defeated by the superior forces of Philip H. Sheridan. The Siege of Petersburg would last from June 1864 until April 1865. General-in-chief (1865) On January 31, 1865, Lee was promoted to be general-in-chief of Confederate forces. As the Confederate army was worn down by months of battle, a Union attempt to capture Petersburg on April 2, 1865, succeeded. Lee abandoned the defense of Richmond and sought to join General Joseph Johnston's army in North Carolina. His forces were surrounded by the Union army and he surrendered to General Grant on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Lee resisted calls by some subordinates (and indirectly by Jefferson Davis) to reject surrender and allow small units to melt away into the mountains, setting up a lengthy guerrilla war. After the WarWashington and Lee University (1865-1870) Following the war, Lee applied for but was never granted the official postwar amnesty. After filling out the application form, it was delivered to the desk of Secretary of State William H. Seward, who, assuming that the matter had been dealt with by someone else and that this was just a personal copy, filed it away until it was found decades later in his desk drawer. Lee took the lack of response, either way, to mean that the government wished to retain the right to prosecute him in the future. Lee's example of applying for amnesty was an encouragement to many other former members of the Confederacy's armed forces to accept being citizens of the United States once again. In 1975, President Gerald Ford granted a posthumous pardon and the U.S. Congress restored his citizenship, following the discovery of his oath of allegiance by an employee of the National Archives in 1970. Lee and his wife had lived at his wife's family home prior to the Civil War, the Custis-Lee Mansion. It was confiscated by Union forces and is today part of Arlington National Cemetery. After his death, the courts ruled that the estate had been illegally seized, and that it should be returned to Lee's son. The government offered to buy the land outright, to which he agreed. He served as president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia, from October 2, 1865. Over five years he transformed Washington College from a small, undistinguished school into one of the first American colleges to offer courses in business, journalism, and Spanish. He also incorporated law into the academic curriculum -- at the time an odd concept, because the law was seen as a technical rather than intellectual profession. He also imposed a sweeping and breathtakingly simple concept of honor — "We have but one rule, and it is that every student is a gentleman" — that endures today at Washington and Lee and at a few other schools that continue to maintain absolutist "honor systems." Importantly, he focused the college on attracting students from the north.

On the evening of September 28, 1870, Lee fell ill, unable to speak coherently. When his medical doctors were called, the most they could do was help put him to bed and hope for the best. Although not diagnosed by his doctors, it is almost certain that Lee suffered a stroke. In his last few years, he had complained about chest pain (probably angina pectoris) and often complained about pain in his right arm, which he said often felt numb. Likely he was developing arteriosclerosis or a type of cardiovascular disorder, and it would gradually weaken him the rest of his life. In the last year of his life, an aged and weak Lee confided to friends that he felt like he could die at any moment. The stroke damaged the frontal lobes of the brain, which made speech impossible, and made him unable to cough or expectorate, which would prove a fatal problem. He was force-fed food and liquids to build up his strength, but some of these liquids found their way into his lungs, and pneumonia developed. With no ability to cough, Lee died from the effects of pneumonia (not from the stroke itself). He died two weeks after the stroke on the morning of October 12, 1870, in Lexington, Virginia, and was buried underneath the chapel at Washington and Lee University. Father: Henry Lee Mother: Anne Hill (Carter) Lee Marriage:

Children:

Assignments:

|