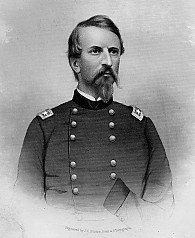

Philip Kearny

Philip Kearny (1815-1862) - Born 2 Jun 1815, New York City. , Died 1 Sep 1862 in Chantilly, Virginia (2nd battle of Bull Run) Philip Kearny was born on 1 Jun 1815, at 3 Broadway on Manhattan Island. His parents were Robert Kearny and Anne Livingston Reade. Phil expressed an early desire to enter the military but his father and grandfather intended for him to study for a career in law. Kearny studied for the law and graduated at Columbia in 1833 and entered the law firm of Peter Augustus Jay in New York City. His grandfather died in 1836 at the age of 87 and left the 22‑year‑old Kearny a millionaire in his own right. So when Kearny announced he was joining the army, there was nothing his father could do. Early Army CareerKearny called on the assistance of his uncle, Lieutenant Colonel Stephen Watts Kearny, as well as the even more prestigious General Winfield Scott, whom he had met and impressed while in school. The newly commissioned 2nd Lt. reported to his uncle at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas, on 10 Jun 1837, and served with the 1st U.S. Dragoons for the next two years protecting settlers and pioneers traveling west. Kearny was a popular officer, a fine horseman, and was quick to praise and reward those under his command. His fellow soldiers could never understand why someone of his wealth and background would volunteer for the rigors of army life, but they enjoyed the benefits of serving with him, as he often used his wealth to ensure his unit was the best outfitted and supplied in the United States Army. After a few years in the field he was assigned as an aide-de-camp to the military district commandant, Brigadier-General Henry Atkinson. Kearny may not have been too happy about his new assignment, but it did have one important benefit; the commandant's beautiful sister-in-law, Diana Bullitt. There was an instant attraction between Diana and Phil, and soon the two were inseparable but an overseas assignment interrupted the romance. In 1839 he went to France with two other officers to study military tactics at the Royal cavalry school, at Saumur. After six months of this experience he went to Algiers as honorary aide-de-camp to the Duke of Orleans, and was present in several notable exploits while attached to the First Chasseurs d'Afrique in the campaign against Abd-el-Kader, the Arab chief. With the death of his father, he inherited a second fortune and was now one of the richest men in America. When he returned to active service, fresh from the excitement of Algiers, he requested a field assignment out west, but was instead sent to Washington D.C. as aide-de-camp to Gen. Alexander Macomb, commander-in-chief of the U.S. Army, and to his successor, Gen. Winfield Scott, 1840-44. Diana Bullitt must have forgiven him for his abrupt departure, for they resumed their romance and on 24 Jun 1841, they were married in a lavish ceremony. He was assigned to Fort Leavenworth and accompanied the expedition through the South Pass, 1844-46. Kearny found this duty as unfulfilling as the previous ones spent in Washington. Not even the birth of his first son in 1845 could raise his spirits or heal the widening rift with his wife Diana. Mexican WarIn 1846, he decided he had had enough with army life and decided to resign from the Army and settle down in New York City. When the Mexican War broke out he withdrew his resignation and recruited a company up to the war footing at Springfield, equipped it magnificently and operated at first along the Rio Grande, but later joined Gen. Scott on his march to Mexico, the company acting as bodyguard to the general-in-chief. Kearny was promoted captain in Dec 1846, and distinguished himself at Contreras and Churubusco, and at the close of the latter battle, as the Mexicans were retreating into the capital, Capt. Kearny, at the head of his dragoons, followed them into the city itself. His left arm was badly wounded and later that day, as Brigadier General Franklin Pierce (later President) held him down, his arm was amputated and was granted a battlefield promotion to Bvt. Major. On returning to New York, he was presented with a splendid sword by the Union Club. Between YearsMajor Kearny spent the next six months at home in New York. He was given a hero's welcome and for the next three years served as recruiting chief in the city. His wife Diana did not so easily forgive what she considered desertion on his part. As Kearny rehabbed and learned to function with only one arm, their troubles escalated. Not even the birth of another daughter could stop the constant bickering between them. Finally almost exactly two years to the day of his wounding in Mexico, she left New York. Although it was thought at the time to be temporary, they never again lived together. After only eight years of marriage, she had had enough. He continued his recruiting duties and rehabilitation, and eventually was able to overcome his disability, even riding a horse with his old abandon holding the reins in his mouth while he used his right hand to hold his sword. His dissatisfaction with the army continued unabated. Finally in July, 1851, Kearny received orders to rejoin his old command, the 1st U.S. Dragoons, in California, just in time to confront the Rouge River tribe that had gone on a rampage attacking farms and settlers. Kearny marched his men to Oregon and routed the warriors ending hostilities. Never an easy man to deal with, he had become increasingly hostile and ambivalent to his superiors, openly questioning their judgment and qualifications. It may not have helped matters that his estranged wife was the sister-in-law of the respected, late General Henry Atkinson. Not even his mentor and friend, General Winfield Scott could assist him with his ambitions. Finally, Kearny admitted defeat and resigned his commission in Oct 1851. Kearny's military career may have been over, but he was still young (36) and rich. He immediately began a world tour which eventually culminated in his beloved Paris, where he had so enjoyed himself a decade earlier. His heroic reputation there, first formed from his adventures in Algiers, had only increased with the news of his courage in Mexico and Oregon. It was there he came upon a young twenty-year‑old engaged woman by the name of Agnes Maxwell, daughter of the customs collector at the port of New York City. She was visiting Paris from her home in New York City. Kearny forgot about his wife and four children, and Agnes forgot about her husband-to-be, and they began openly living together in Paris. His legal and embarrassed wife, Diana, angrily refused a divorce when he visited her in 1854. By 1855, Agnes and Kearny had left New York to settle in his new mansion, Bellegrove, overlooking the Passaic River in what is now Kearny, New Jersey. They had come here to escape the disapproving tongues of New York society. Bellegrove was located only a short distance and across the river from his family's old manor in Newark. In 1858, Diana finally acceded to his demands for a divorce. In 1859 he traveled to France again and volunteered for the campaign against Austria that year. He fought with tremendous courage and distinction and when again offered the Legion of Honor, he accepted becoming one of the first Americans so honored. He stayed in Paris until 1861, when the outbreak of the U.S. Civil War spurred him to returned home to offer his service to the Union. U.S. Civil WarHis reputation for difficulty seemed to overshadow his reputation for courage and leadership. When he realized he was not going to be granted a commission in the army he tried to join as a lowly private, but was again rejected because of his infirmity. In July, 1861, New Jersey commissioned him as a Brigadier General, and placed him in command of the New Jersey Brigade stationed near Alexandria, Virginia. He found his new brigade barely trained and undisciplined. He immediately began to change that with constant drills and marches while awaiting the seemingly never to be fought battles. He was tough, but he was fair, and he always looked out for his men, making sure they were properly fed and outfitted even at his own personal expense. He was subsequently given by President Lincoln a commission as brigadier-general of volunteers, to date from May 17, 1861, and was assigned to command the 1st N. J. brigade in Gen. William B. Franklin's division, Army of the Potomac. Gen. Kearny was present at the battle of Williamsburg, where, arriving at 2:30 p. m., he reinforced Gen. Hooker's division, recovered the ground lost and turned defeat into victory. He served through the engagements of the Peninsula, then, with the Army of Virginia, from Rapidan to Warrenton. He was given command of a division in May, 1862, and was given a commission as major-general of volunteers to bear the date of July 4, which, however, never reached him. At the second battle of Bull Run he was in command on the right and forced Jackson's corps back against Gen. Longstreet's men.  He was killed on the battleground of Chantilly, Virginia, 1 Sep 1862. While reconnoitering, he had inadvertently penetrated the Confederate lines and was trying to escape when he was shot through the spine and instantly killed. His remains were sent by Lee under flag of truce to Gen. Hooker. General Kearny was organizing a reinforcing action for General Isaac Stevens who was also killed that same day. The body was then sent to Washington for embalming, and then to his home, Bellegrove where it lay in state. On 8 Sep 1862 Kearny was paraded and honored for a final time, first in Newark and then in Jersey City. He was then brought by ferry to New York City and after services buried in the family crypt at Trinity Church. In 1912 his body was moved to Arlington National Cemetery where an elaborate memorial was built.

Father: Robert Kearny (1783-1832) born 8 Dec 1738. Died 14 Mar 1832. Mother: Anne Livingston Reade (1783-abt 1822) Marriage:

Children:

Assignments:

Personal Description:

Source:

References:

|